Using Willow in Permaculture: Living Fences & Biomass

At a local nursery, I came across a grafted Salix integra—commonly known as flamingo willow—for its eye-catching pink-tinged foliage. While it’s often grown as a decorative shrub, I saw something far more functional in this small tree: the beginning of a broader, multi-functional plan rooted in using willow in permaculture systems.

From the outset, this willow will be transplanted and given time to establish itself.

This willow is the first step in what I envision as a living system of resilience:

- Propagating cuttings to create living fences

- Establishing a system for pollarding to harvest renewable wood

- Using biomass for mulch and woodchip production

- And eventually, crafting a natural rooting hormone from the willow itself

Each of these functions emerges from a single plant, making it a textbook example of permaculture’s ethic of “care for the Earth, care for people, and fair share.”

This story will follow how one small act of planting can evolve into a system that benefits the whole garden.

Why Willow Is Ideal for Permaculture Systems

Willow (Salix spp.) is a genus with exceptional potential in sustainable systems. It offers a rare combination of rapid growth, regenerative ability, and diverse functionality, making it one of the most adaptable species for both ecological restoration and low-maintenance cultivation.

According to the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, willows are highly effective in stabilizing streambanks, improving soil health, and restoring degraded sites. Their rapid rooting ability, even from dormant cuttings, makes them invaluable for erosion control and agroecological applications.

For a permaculture-oriented site or garden, willow brings several advantages:

Functional Benefits of Willow

| Purpose | Benefit |

|---|---|

| Propagation | Cuttings root readily in moist soil without the need for rooting agents |

| Living Fences | Dense growth and pliable stems allow for weaving, shaping, and layering |

| Pollarding/Coppicing | Yields high biomass for fuel, mulch, and structural material |

| Soil Building | Leaves and chipped branches decompose quickly, enriching organic matter |

| Biodiversity Support | Supports native pollinators, birds, and beneficial insects |

Willows are especially valued in regenerative agriculture systems for their short rotation cycles—many species can be pollarded every 2–3 years without compromising health. This rapid regrowth ensures a continuous supply of woody biomass for mulch or composting while also encouraging strong root systems that anchor the soil.

Willow bark also contains natural compounds like salicylic acid and indolebutyric acid, both of which promote rooting and reduce transplant stress. As explained by the University of Illinois Extension, steeping young willow stems in water creates a simple, effective rooting solution for plant propagation—an age-old technique with modern relevance.

The decision to work with willow isn’t just about choosing a hardy tree—it’s about selecting a keystone species that can serve multiple roles across your landscape. Its value compounds with time.

Transplanting Willow in a Permaculture Garden

Before this willow can begin its role in a larger system, it first needs to take root—literally. Transplanting a grafted willow like Salix integra ‘Flamingo’ calls for particular care. While most willows are resilient and quick to adapt, grafted cultivars have two genetic layers: the rootstock and the scion. Ensuring both thrive in a new location starts with choosing the right conditions.

Site Considerations

Willow prefers:

- Moist but well-drained soil

- Full sun to partial shade

- Adequate space for lateral root spread and above-ground shaping

In my case, I’ve planted mine on a steep hillside with sandy soil. It receives direct sun during the morning and afternoon, which should encourage strong growth while allowing the soil to dry between rainfalls. Although it’s positioned fairly close to my neighbor’s property, I’ve planned for that: because it’s a grafted tree, I won’t be coppicing it. Instead, I’ll pollard it regularly to keep it small and manageable, avoiding unwanted shade or obstruction.

My particular specimen is grafted quite high—approximately 40 cm (16 inches) above the base—and shaped to form a round, ornamental canopy. Because of this elevated graft, there’s no risk of burying it unintentionally, which simplifies planting.

Handling the Graft

For most grafted trees, it’s important to plant above the graft union, typically visible as a bulge or scar low on the trunk. Burying the graft can encourage the rootstock to dominate. In this case, with a high graft height and clear visual separation between scion and rootstock, the concern is minimal—but it’s still important to monitor the base for any rootstock suckers.

Establishment Period

For the first season, the focus is observation:

- How does the tree respond to the site?

- Is it showing strong vertical or lateral growth?

- Are there signs of rootstock suckers or stress?

Willow’s fast feedback loop means that within a few weeks, you’ll begin to see whether the planting site is suitable. This early-stage monitoring will also help determine the best time to take cuttings for propagation later in the season.

Once established, this willow will no longer be a stand-alone feature—it becomes a working element in a living, responsive system.

Using Willow Cuttings for Living Fences

One of the most practical and rewarding uses of willow in a regenerative garden is its extraordinary ease of propagation. Unlike many woody plants, willow doesn’t require rooting hormone or specialized techniques. Cuttings taken during the dormant season can be planted directly into moist soil, where they will often take root with minimal intervention.

This natural rooting ability is what makes willow especially valuable for creating living fences—dense, woven rows of closely planted cuttings that can serve as both structure and shelter within the landscape.

Why Living Fences?

Living fences offer more than just boundaries. They:

- Act as windbreaks, reducing erosion and moisture loss

- Provide habitat for birds, beneficial insects, and amphibians

- Enhance privacy while remaining permeable to light and air

- Can be shaped over time through weaving or pruning

- Contribute biomass for mulch or composting after seasonal trims

In permaculture systems, structures that serve multiple purposes are highly valued. A willow fence isn’t just a barrier—it’s also a productive plant, a carbon sink, and a wildlife corridor.

My Approach

While my current willow is grafted and primarily ornamental, I plan to take cuttings from the scion, which retains the variegated foliage of Salix integra ‘Flamingo’. These will be used to establish the first rows of a living fence. Cuttings from the rootstock (if any appear) will be avoided, since they likely won’t share the same growth or aesthetic traits.

I’ll space the cuttings roughly 20–30 cm (8–12 inches) apart in double or staggered rows, depending on the layout. Once rooted and growing, the young shoots can be:

- Woven together to create a lattice structure

- Tied and bent into arches or domes for sculptural interest

- Trimmed annually to encourage denser growth and maintain shape

The flexibility of willow allows for long-term experimentation. Over time, some of these fences may evolve into shaped hedgerows or even serve as wind-buffered corridors for delicate crops.

Timing and Tools

The ideal time for propagation is during late winter or early spring, before the plant breaks dormancy. Hardwood cuttings should be:

- 20–30 cm (8–12 inches) long

- Taken from healthy, pencil-thick shoots

- Planted with at least two-thirds below ground

As the cuttings root and grow, they’ll begin to fulfill their structural role—no nails, wire, or hardware required.

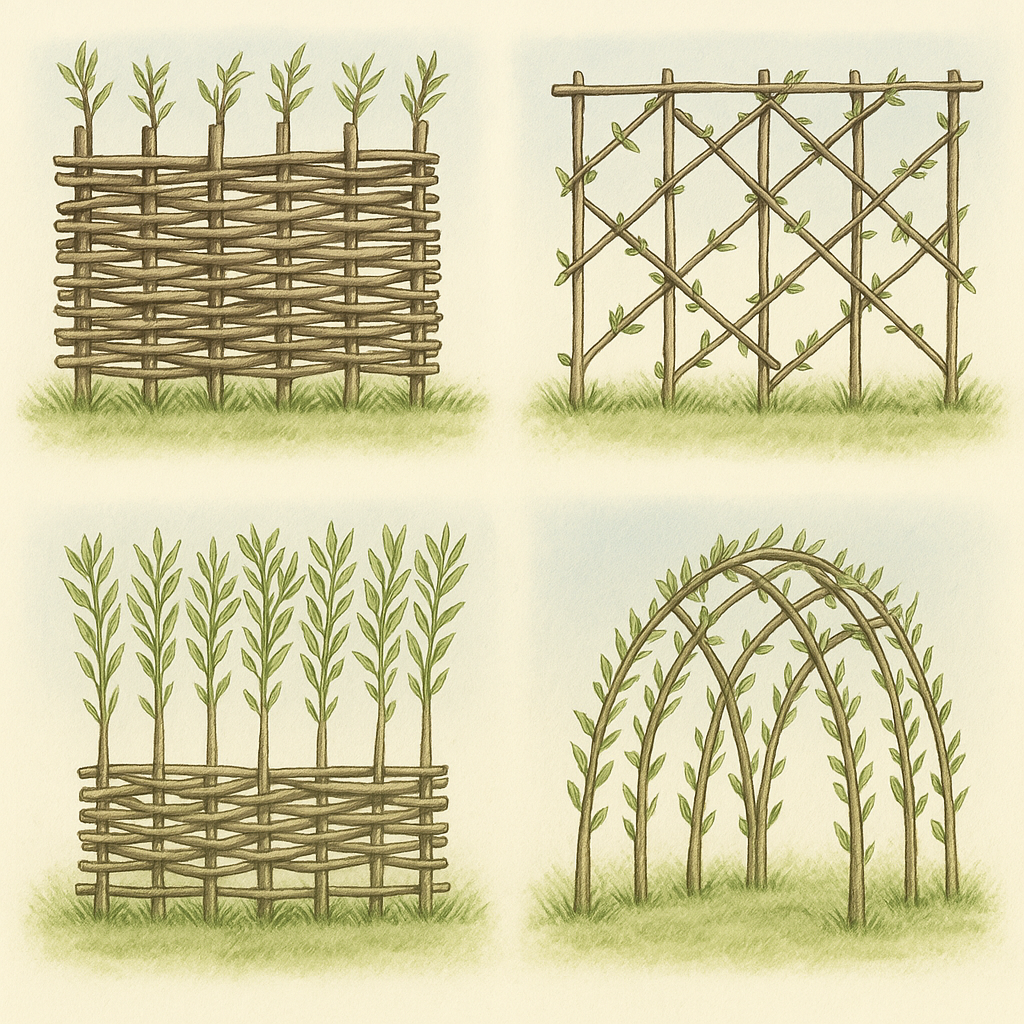

Visual Inspiration: Living Willow Structures

While I’m still in the early stages, here are a few concepts I’m considering for future living fence and structure designs. The image below shows examples of what’s possible when willow is trained, woven, and pollarded over time:

These forms—ranging from wattle-style fences to woven domes and espaliered hedges—represent potential directions I may pursue as my propagated willow cuttings take root and mature. Once I begin shaping the actual structures, I’ll update this page to document the process, techniques, and outcomes.

For now, this AI illustration serves as a starting point and a reminder that regenerative design evolves through experimentation.

Pollarding Willow for Biomass in Permaculture

As the willow matures, one of the long-term goals is to manage it through pollarding—a traditional method of pruning that allows for repeated harvests of new growth while maintaining a compact and controlled tree form. Unlike coppicing, which cuts the tree back to ground level, pollarding preserves a permanent trunk and is especially well-suited for grafted trees like mine.

Why Pollard?

Pollarding offers several advantages in a garden or permaculture system:

- Controls height and spread, making it ideal near boundaries or structures

- Encourages vigorous, uniform regrowth

- Allows for cyclical harvesting of young, straight branches

- Keeps biomass production high without sacrificing tree health

- Prevents shading of nearby areas, including neighbor’s property

In my case, pollarding also serves a practical neighborly function. Since the tree is planted fairly close to the property line, maintaining a small canopy through annual pruning ensures I won’t be imposing a large, dense tree in front of their view or windows.

Biomass as a Resource

Each pollarding cycle will produce a generous volume of young wood and leafy material—biomass that can be used across the site. These cuttings can serve multiple roles:

- Chipped for mulch, enriching garden beds and suppressing weeds

- Composted, contributing carbon-rich material to balance nitrogen-heavy inputs

- Used in raised bed walls or pathways for natural edging or erosion control

- Fed to fungal beds, especially species like Stropharia rugosoannulata (wine cap mushrooms) that thrive on woody mulch

I’ve actually tried inoculating several areas of our garden with wine cap mushroom spores. I ordered spores and applied them in different woodchip-heavy spots. Something did grow—but it looked nothing like the Stropharia mushrooms I’d seen in illustrations or guides. Since proper identification is essential, we chose not to use them in the kitchen. Hopefully, I’ll be able to find a more reliable and identifiable source in the future and revisit this idea with greater confidence.

Wine Cap Mushrooms (Stropharia rugosoannulata)

Timing and Method

The best time to begin pollarding is after the tree has become well-established—usually 2–3 years after planting. For grafted trees like mine, it’s important to:

- Pollard above the graft union to preserve the desired variety

- Use clean, angled cuts to reduce risk of disease

- Maintain a consistent framework so future regrowth is manageable

Once a rhythm is established, this tree will provide a steady supply of biomass for years to come—all from a simple seasonal task that enhances its structure, rather than depleting it.

What’s Next for This Willow in the Permaculture Plan

For now, the willow is settling into its new hillside location. Over the coming months, I’ll monitor how it responds to the sandy soil, sun exposure, and slope—looking for signs of strong establishment before moving on to propagation and structure-building.

If all goes well, the next phases will involve:

- Taking cuttings from the scion wood to begin testing layouts for living fences

- Establishing a pollarding schedule once growth is vigorous enough

- Experimenting with biomass use in mulch, composting, and soil-building projects

There’s also the longer-term goal of making a natural rooting solution from the willow itself. But I’ll hold off on sharing that process until I’ve tested it firsthand.

This project may have started with a single tree, but it reflects the kind of long-term thinking that underpins a resilient garden. I’ll update this post as the system begins to evolve—and as always, welcome feedback from others working with willow in similar climates or conditions.

More on Perennial Plants in Permaculture

f you’re interested in multifunctional trees that go beyond beauty and offer real value in regenerative systems, take a look at another profile on a favorite of ours:

Plant Profile: Mulberry – The Versatile Tree for Every Sustainable Garden

Mulberries are fast-growing, resilient, and productive—perfect candidates for food forests, living fences, and soil improvement. Like willow, they fit seamlessly into systems designed for both abundance and low input.